What can we learn from analyzing news coverage of the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Sarah Valentin, a PhD in veterinary health informatics, worked with a team of epidemiologists and researchers at CIRAD, France, including Elena Arsevska, Alizé Mercier, Renaud Lancelot, and Mathieu Roche, to find out whether an assessment of news reporting can help us to detect similar outbreaks in the future.

In order to assess the nature of news reporting, the team used PADI Web, an online media monitoring tool originally developed to assist French veterinary services in monitoring animal infectious diseases threatening the French territories, according to Sarah.

Through PADI Web, online news were collected from RSS feeds on specific animal infectious diseases and non-specific symptoms over the period ranging from Dec 31, 2019 – Jan 26. None of these feeds were dedicated to COVID-19 as it was a new disease, however, signals of this disease emergence were still captured by the tool.

The collected online news was then cleaned and translated into English. As this project required an immense amount of translation and data processing work, it was important to find effective translation methods that work for various Chinese dialects and languages.

Thus, PADI-web integrates a multilingual model to include news in any language the team deemed necessary for translation.

“We rely on an automatic translator from Microsoft, and indeed, there has been great improvement in automatic translation over the last few years,” said Sarah.

Once processed, each collected online news is then classified and categorized as relevant or irrelevant. In this step, the problem of fake news is resolved by humans, or more specifically in this case “by experts who can verify the reliability of the source,” Sarah explained.

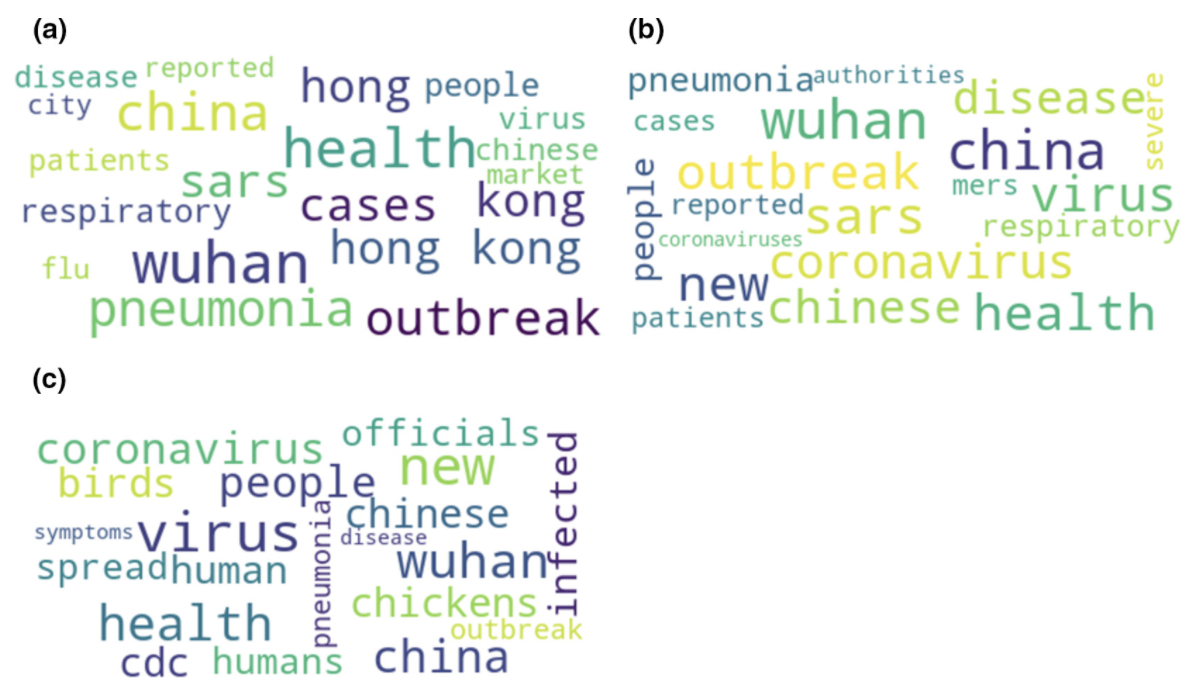

The team then extracted the information pertaining to COVID-19 messaging. The results revealed two clusters of news, almost equally distributed.

The first group comprised 55 percent of feeds which included disease-specific terminology, meaning wording such as “influenza,” or “African swine fever.” One of the reasons for these findings was that the study period analyzed overlapped with outbreaks of avian influenza which had reached a culprit in China before COVID-19 was truly identified.

The other group, consisting of non-specific feeds such as mentions of symptoms, species names and other terminology related to the “unknown” or “mysterious” as classified by the team, represented 45 percent of feeds.

The fact that disease-specific classifications had reached a level only slightly surpassing that of “unknown” over the examined time period came as a surprise to the team.

The emergence of specific vocabulary is crucial, including journalistic language when trying to detect public health emergencies, according to Sarah.

The media’s learning curve is illustrated in the following graph depicting how before official identification of COVID-19, between 70 and 90 percent of terminology was related to symptoms or unknown disease aspects.

This changed rapidly following January 9, when official identification of COVID-19 led to a mostly continuous increase in disease-specific language and terminology used across media outlets.

Once human-to-human transmission was confirmed, technical language referring to medical methodological approaches to prevent the spread of the virus increased as well.

“The team was debating which terms to monitor, and at first, of course, we focused on medical terms because we were all [researchers] from the animal health domain,” Sarah said.

For some time, they even excluded terms from the “mysterious” and “unknown” domains, but soon they realized that in the process of identification and reporting, this way of writing was as important as medical terminology.

In fact, non-medical terms can be “more specific during this period of emergence,” according to Sarah.

The study conducted of course was retrospective, knowing that COVID-19 had occurred already.

This is why Sarah suggested that a set of feeds specific to the period of emergence with specific text mining weighting methods such as TFIDF could be created to further enhance the functionality of PADI Web in early detection.

The tool, which is currently being used in MOOD complementary to systems such as ProMED and HealthMap, could then help to better isolate terms indicating early warning signals. In addition, more filters could be applied to create more fine-grained alerts.

“So the challenge will be to create alerts on a daily basis maybe by evaluating the number of words of certain categories in order to react in more prospective ways and to compare these signals in different systems, because we also noticed that the different systems detect the same signals through different sources. Eventually we could hopefully then convert this detection into early action,” said Sarah.