How will different African countries be affected by the spread of COVID-19 and what can we learn about its importation and exportation patterns across the African continent?

In mid-January 2020 MOOD researchers examined the threat of COVID-19’s spread throughout the world through international travel amid fears of a potential high escalation risk scenario.

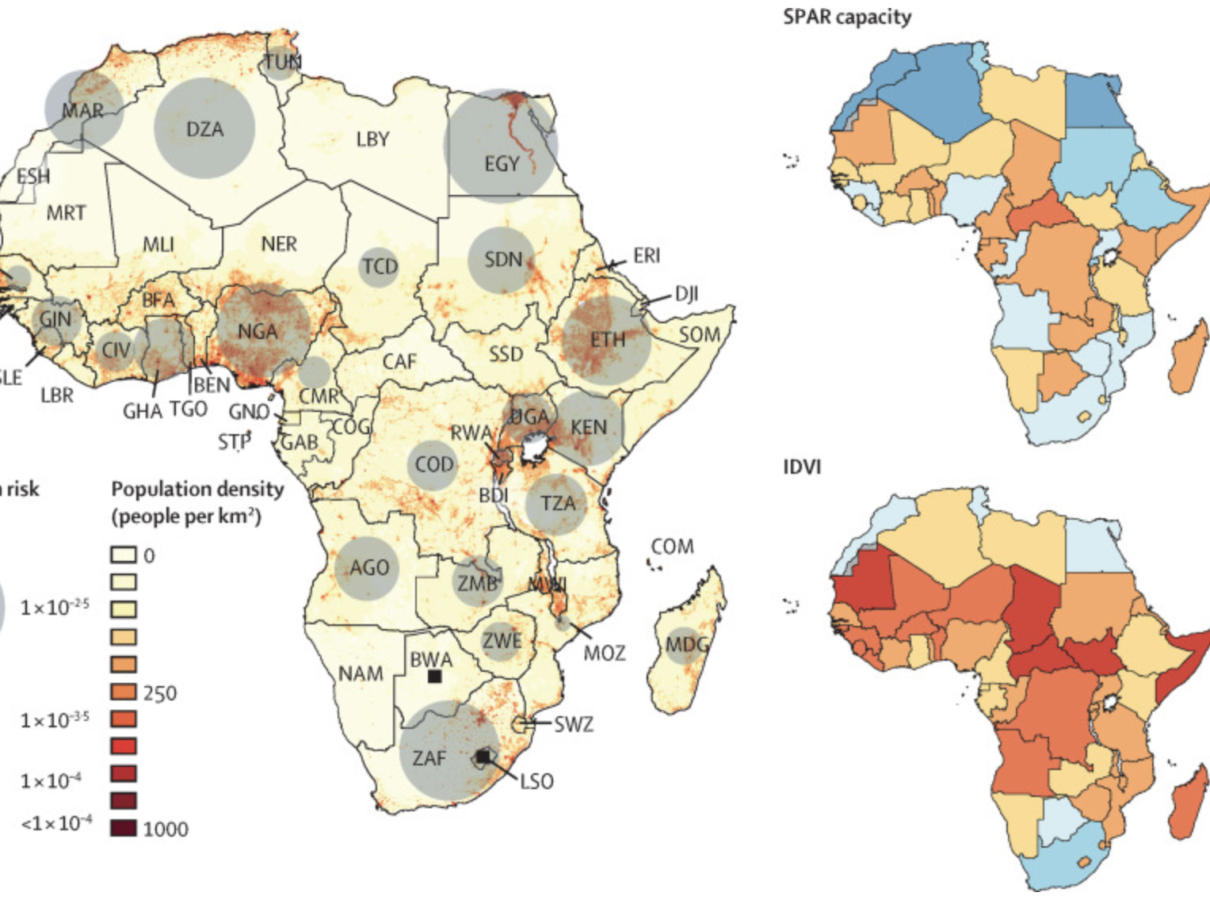

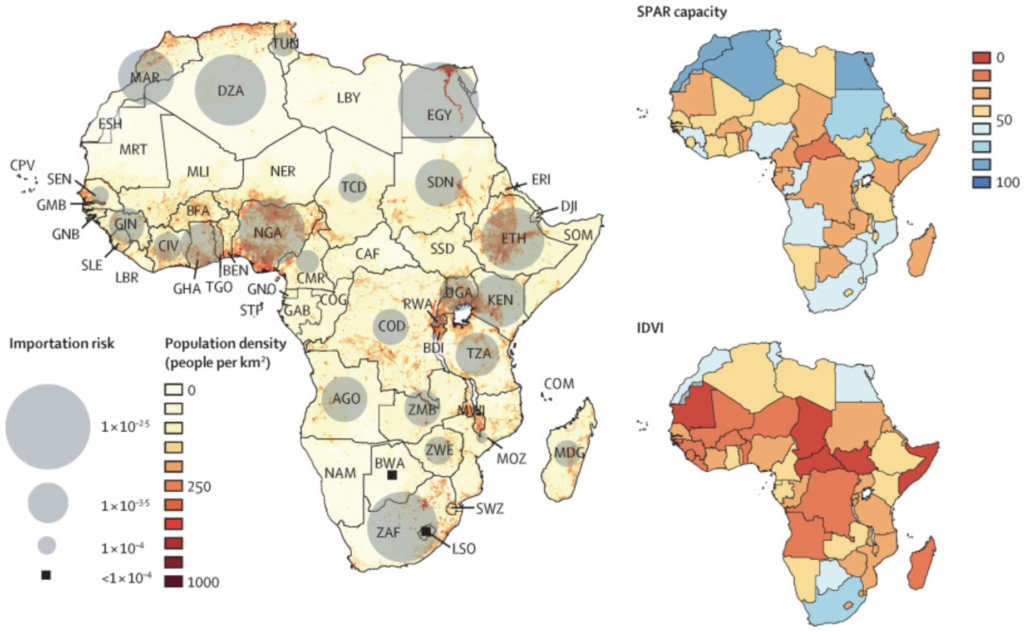

In February, the team led by INSERM Research Director Vittoria Colizza and Marius Gilbert, researcher at the Spatial Epidemiology Laboratory at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, published their findings that African countries standing at a high risk of importing the virus had a moderate to high capacity to respond to outbreaks, while countries at a moderate risk had variable capacity and high vulnerability to outbreaks.

The authors of the study report highlighted that “resources, intensified surveillance, and capacity building should be urgently prioritized in countries with moderate risk that might be ill-prepared to detect imported cases and to limit onward transmission.” And indeed, the results imply that many African countries were stepping up their preparedness for early detection of and dealing with Covid-19 importations at the time of publication. It appears that, at least so far, this preparedness has prevented massive mortality events on the continent.

Marius Gilbert acknowledged that the overall number of COVID-19 cases were most likely underreported in many African countries, but he emphasized that it’s unlikely that a scenario of excess mortality would have been missed in Africa. “If people start dying, especially older people who are well-respected in family structures, if there had been cases of excess mortality, we would have known,” he said.

Scientists involved with the project used different sets of indicators to measure individual countries’ preparedness for COVID-19. Some of the measures used, such as the WHO IHR MEF’s Joint External Evaluation and the State Party Self-Assessment Annual Reporting, or SPAR for short, relied – as the names imply – on indicators stemming from self-evaluation provided by the respective countries’ leadership. They aim to measure the functionality of health systems that were already in place at the start of the pandemic. Of course, such an assessment can be imprecise and flawed for a number of reasons as there may be plenty of motivations or unintended misinterpretations that could lead countries to over- or underestimate their own preparedness.

In order to compensate for this and to take additional important factors into account, the researchers also employed the Infectious Disease Vulnerability Index (IDVI) as well as the INFORM Epidemic Risk Index. “One single index can rarely capture anything, … when you see convergences in the (overall) picture with different indices, then you know that there is probably something behind it,” said Gilbert. In other words, if several indices tell you at the same time that a country is particularly vulnerable, then that is probably the case.

In order to illustrate where COVID-19 spread could have the most extensive, rapid, and detrimental effects, the researchers overlaid the importation rates with each country’s population density. “If you have a similar risk of introduction, the potential impact in a higher populated country is much higher than in a country with much lower population density. We’ve also learned that the spread was more successful in highly populated areas. It’s one of the reasons why [in Europe] Belgium was so strongly affected,” said Gilbert.

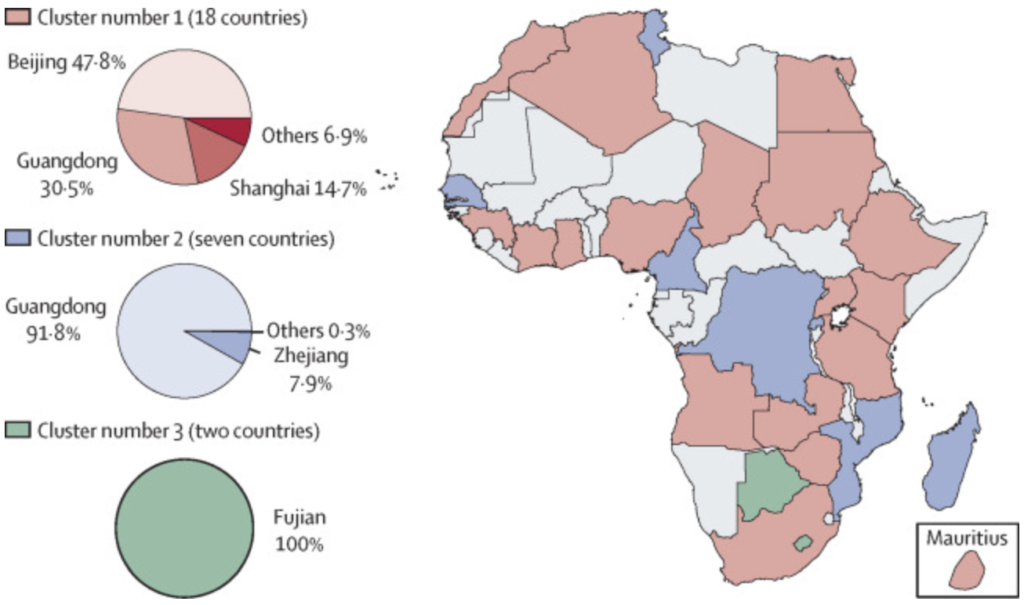

The scientists also found that there were three clusters of countries within Africa that stood at a comparable risk of importation from specific Chinese provinces. In Gilbert’s words: “it was grouping together the African countries that share the same passenger flows with the same sets of Chinese provinces.” This means that at a time when public discussion revolved around Wuhan, the researchers attempted to also illustrate the geographic disparities in global interconnection and travel patterns that could lead to transmission of the virus from different areas depending on individual African countries.

When looking back at the study’s estimations, Gilbert emphasized that the researchers’ predictions for ’high risk’ areas mostly matched outcomes of the first phase of the pandemic. However, he also stressed that there were some positive surprises as the pandemic continued to spread.

“What we did not expect was this relatively low level of epidemic development in terms of impact of excess mortality,” he said. He explained that on the one hand, this may have been due to the favorable age distribution in African populations which makes them less vulnerable compared with populations in Europe. At the same time, researchers had feared that the overall less advanced state of African health systems – when it comes to factors such as beds per inhabitant and ICU pads available – would still reverse this advantage. Nonetheless, the impact in terms of excess mortality in most African countries has been relatively limited, certainly lower than what people were fearing, according to Gilbert.

“It really teaches us modesty that we need to be very careful in our assessment. It’s not only a matter of temperature or humidity either, because you also have a very serious epidemic for example in South America… So, there are factors that we do not fully understand that may have prevented the worst epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa and it’s really something we’ll need to understand in the years to come,” he said.