The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated how rapidly incorrect information about vaccines can emerge and evolve online, fuelling hesitancy to national vaccination campaigns within the European Union. Behavioural studies show that the way communities perceive and understand vaccines play a major role in influencing people’s behaviour and trust, including with respect to COVID-19 vaccinations, posing serious challenges to national and international vaccination efforts.

With less than 75% of fully vaccinated European citizens for COVID-19, and new threatening variants spreading around the world, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) is calling out attention to vaccine hesitancy and misinformation as serious risks for public health. Over the past years in fact, experts at ECDC have seen a concerning growing trend in factually or scientifically incorrect information circulating online, causing a lot of doubts in users regarding the trustworthiness of health-related information, and vaccines.

Vaccine misinformation has been, and still is rapidly evolving and spreading on popular platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook, impacting on people’s trust in the “effectiveness and the side-effects of vaccines” and their acceptance, explained John Kinsman, expert in Social and Behaviour Change Communication at ECDC, and author of a recent study addressing vaccine misinformation across 6 states in Europe.

Watch the webinar here: https://av.tib.eu/media/54894

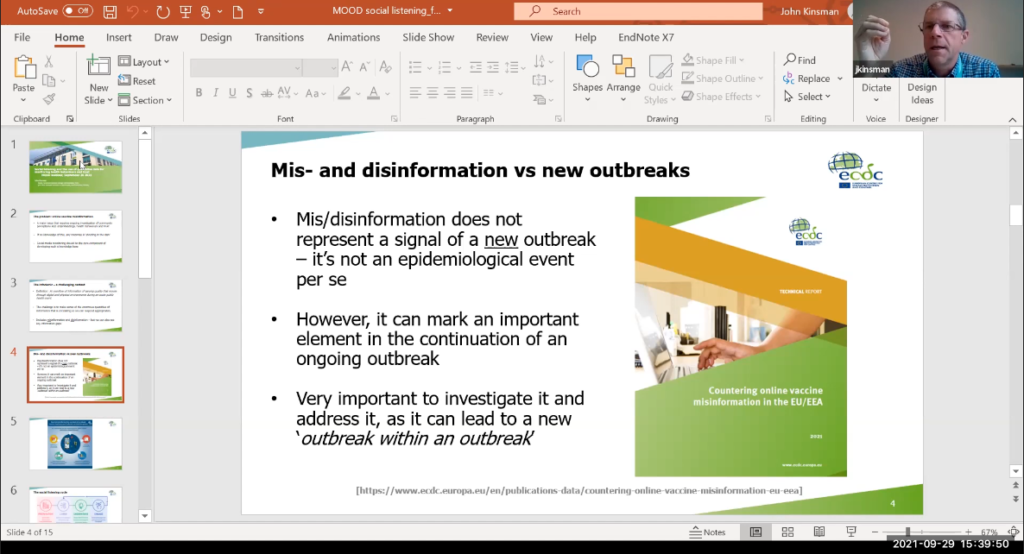

As John presented during our last MOOD Science Webinar, the study provides science-based insights on the factors behind vaccine hesitancy and misinformation, as well as actionable guidelines to adopt in national response strategies.

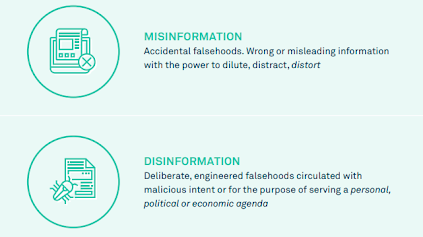

More than a year ago, the World Health Organization warned of a COVID-related “infodemic”, raising concerns about the ‘overflow of information of varying quality that moves through digital and physical environments during an acute public health event’. And concerning is also the number of studies demonstrating the overwhelming exposure of users to unreliable, unchecked, or even intentionally misleading inputs on social media.

One major threat is that fake news spreads faster on social media platforms, fast-paced, popular, uncontrolled environments, than verified and validated news from credible sources. This type of phenomenon is not new to social scientists like John, who has long been studying community hesitancy to HIV, Ebola, and other infectious diseases treatments across Africa.

From Misinformation Management Guide 2020.

Although the infodemic waves are not considered as epidemiological events themselves, rather a behavioral phenomenon evolving on the media, they can indirectly link to an actual epidemic outbreak: the spread of distrust in vaccine effectiveness and their side-effects can lead to critical decisions and behavioural reactions that limit the vaccine uptake from the population, thus increasing the epidemic risk.

Moreover, “many countries do not have a very sophisticated system for monitoring online vaccine misinformation”, added John, most likely due to lack of resources and capacities, posing a big constraint on national misinformation monitoring systems.

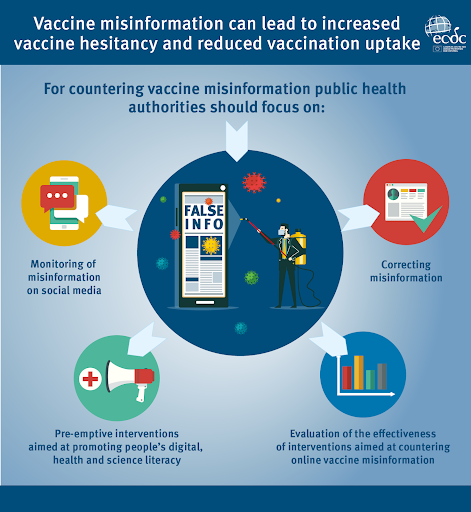

If misinformation is seriously threatening the vaccine uptake from the populations and posing serious risks to prevention efforts, how can we then counter the circulation of fake news to regain trust?

Chasing misinformation

In consideration of the challenges faced by national health authorities, John and his team were tasked to explore the main sources of online vaccine misinformation across the European continent, and the evidence base for how to counter online vaccine misinformation.

“You can’t address online misinformation, unless you know the particular type of misinformation that would be disseminated”, explained John, together with the kind of messages and information, the channels and who are the actors involved. With such a broad context, and massive quantities of information spread, the role of social scientist becomes crucial in applying complex, specialized methodologies to reach a fair understanding of the causes in people’s distrust.

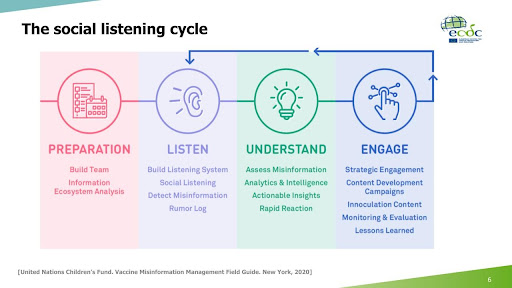

Vaccine hesitancy has been the subject of UNICEF campaigns, which supported the development of the ‘social listening cycle’ technique, a system for ‘listening to social, and other media” which filters out epidemic-related content on major social media platforms.

cooperative to ensure coordination of all actions and actors.

While the UNICEF framework takes a broader perspective, defining in rough terms an entire programme for social listening and addressing online misinformation, the work conducted by John at ECDC focussed on developing a training specifically for public health experts and risk communication practitioners in addressing online vaccine misinformation.

As John explained, the study included a literature review, interviews with representatives of national public health authorities from six EU Member States (Estonia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and Romania) and several pan-European and international organisations involved in countering vaccine misinformation, as well as a social media analysis in the six participating countries.

With a mixed-methods approach consisting of qualitative and quantitative research methodologies, the team was able to extract valuable data from social media first, to sieve misinformation from knowledge gaps then, and eventually identified major sources and channels that spread misinformation.

Vaccine trust & messengers

The findings of John’s work, as shown in the presentation, illustrated the extent of variation in online misinformation between countries, constituting a major issue in certain cases. As John remarked: There is an incredible discrepancy between countries in vaccination rates; the top country [in EU] is Ireland with 91% of vaccinated population, and the bottom is Bulgaria with 23%, as for September 2021.

In brief, vaccine uptake varies greatly from country to country, and from time to time, but it often finds common roots in complex social perceptions: the lack of trust to authorities ruling out indications (“I don’t trust the messenger, hence the message is unreliable”), the lack of complacency (“it does not involve me”), and lack of a sense of collective responsibility from groups of individuals (“it’s not my problem”), as John explained.

Despite the ECDC’s efforts in providing timely and accurate data during COVID-19 vaccine rollout, “If you don’t trust who is telling you to get vaccinated, you wouldn’t even think twice” remarked John.

Through social listening, his team observed that people’s response to vaccination campaigns have been strongly influenced by the level of trust in public authorities, also covering the role “messengers” in charge of transmitting health indications during the state of emergency. With little to no trust in the messengers, health messages are often disregarded, leaving room to fake news and individual beliefs.

In an effort to tackle this issue during vaccination campaigns in previous epidemic emergencies, John explained that a lot of work was done to individuate public figures, for example celebrities and sports personalities, which could connect to people and therefore transmit health messages more effectively.

“What we have found out very clearly in our study,” continued John “ is that no matter how you do it or when you do it, the people that are trusted the most with regards to vaccines are health workers”.

To increase vaccination uptake in order to minimize health risks, public health authorities will need to focus on connecting with people, “explaining about risks and benefits of vaccines,” John argued “and taking people’s concerns very seriously”. By working in close contact with people, health-care employees cover an underestimated position, concluded John, and targeted training programmes can be a way forward to rebuild vaccine trust in populations.

What about social media?

On one hand, trustworthy figures are essential in spreading accurate health messages, on the other the ability to receive them and verify their sources is determined by the channels. While social media companies, such as Facebook and Twitter, started to actively tag and remove COVID-19 misinformation in 2021, “much more effort from their side” is needed in John’s opinion.

“Shutting down misinformation” by social media companies presents challenges, as the nature of a piece of fake news is “not often clear”. With “the best technologies in this area, in the world,” big-tech corporations are called upon to share misinformation data with health organizations, medical journals and researchers such as John, to better understand misinformation trends, and improve identification mechanisms.

The way forward

The findings of John’s study have been summarized in actionable guidelines for health authorities, as he stressed toward the end of the presentation. Results and discoveries of the social listening should then be embedded into national health care systems, so that key findings “can be taken out and acted upon”.

In line with the MOOD approach, John also highlighted the importance of integrating diverse disciplines when analyzing data, as “no one single type of data can provide one whole story”.

Combining qualitative research with quantitative analysis lies at the core of MOOD line of work, paving the way to innovative and more effective responses to epidemic outbreaks in Europe and worldwide.

John Kinsman works at ECDC, one of the primary users for MOOD’s tools and services in epidemic intelligence and epidemic event surveillance in a OneHealth context. To counter vaccine misinformation, ECDC has also launched the COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker and it’s available here.

Watch the video recording on https://av.tib.eu/series/1041/mood+science+webinars